Teruma | Chesed as Part of Synagogue DNA

This article first appeared here.

Elli Fischer on Parashat Teruma. Rabbi Elli Fischer '99 is an independent writer, translator, and editor. He was previously the OU-JLIC rabbi at the University of Maryland, and is a founding editor of The Lehrhaus. Rabbi Fischer is the translator of By Faith Alone: The Story of Rabbi Yehuda Amital and the editor of Rabbi Eliezer Melamed’s Peninei Halakha series in English.

In memory of Risa Gittel a”h bat Yosef Zalman HaKohen sheyichyeh

What was the purpose of the Mishkan, the portable Temple that stood at the center of the Israelite encampment in the desert, and for centuries thereafter until the building of the Jerusalem Temple? For that matter, what was the purpose of the Temple itself, the Beit HaMikdash?

In one of the first pesukim of this week’s parsha, Hashem states, “They shall make Me a Mikdash (sanctuary), and I will dwell among them” (Shemot 25:8). This is one of the focal points of the entire book of Shemot. In Ramban’s interpretation, the story of Shemot, the story of the exodus and redemption from Egypt, is about the transformation of a downtrodden, enslaved, and even idolatrous people into a people worthy of having God dwell in their encampment. The book of Shemot concludes with a description of how Hashem’s presence, concealed within a cloud, filled the entire Mishkan, thus completing the transformation.

On this understanding, the focal point of the Mishkan was the Aron HaEdut, the Ark of the Covenant. Hashem is described as “yoshev keruvim” (“seated upon the cherubs”), and in this sense, the Aron was meant to be a throne, as it were, where Hashem’s presence within the community of Israel was most concentrated, and from where Hashem spoke to Moshe: “When Moshe went into the Ohel Mo’ed (Tent of Meeting) to speak with Him, he would hear the voice addressing him from above the cover that was atop the Aron HaEdut, between the two keruvim; thus He spoke to him” (Bamidbar 7:89). In Ramban’s view, the Mishkan was a mobile Mount Sinai; the place from which Hashem continued to communicate with the people of Israel.

In the book of Vayikra, however, the focal point of the Mishkan is the altar, where individual and communal offerings were sacrificed. The altar was the center of our devotion to Hashem. In his codification of the laws of the Mikdash, Rambam places the altar at the center:

The altar’s place is very specific, and its place can never be changed […] There is a universal tradition that the place where David and Shlomo built the altar, on the threshing floor of Aravna, is where Avraham built an altar and bound Yitzchak; and it was there that Noach built [an altar] when he emerged from the Ark; and it was on that altar that Kayin and Hevel brought their offerings; and it was there that Adam HaRishon brought a sacrifice upon his creation; and it was from there that he was created. (Hilkhot Beit HaBechirah 2:1–2)

Thus, we have two focal points of the Mishkan and later the Beit HaMikdash: the Aron, where Hashem “sits,” as it were, and speaks to us; and the Mizbe’ach, the altar, where we worship Hashem. In Shemot, the Aron is emphasized, and in Vayikra, the Mizbe’ach is emphasized.

Fast forward about a thousand years, and for the first time, the people of Israel were left without a Temple, without a central place of worship, without a focal point of Hashem’s presence in the world. Instead of a single, central Mikdash, it was during this period that a new institution began to emerge: the beit knesset or synagogue. The prophet Yechezkel (11:16) already speaks about how Hashem’s presence will remain within the Mikdash me’at—the miniature sanctuary—in the lands where they would end up.

When the Jews returned from exile to rebuild the Mikdash, a group of Sages called the Anshei Knesset HaGedolah, led by Ezra and Nechemiah, instituted some far-reaching changes that relate to the core functions of the Mikdash. Ezra reinforced and augmented the practice of public Torah reading. The same generation of sages ordained the basic outline of our daily prayers, corresponding to the daily offerings in the Mikdash.

The Anshei Knesset HaGedolah were active at the end of the age of prophecy, and they viewed themselves as the heirs of the prophets: “Moshe received the Torah at Sinai […] and the prophets transmitted it to the Anshei Knesset HaGedolah” (Avot 1:1). In their era, the primary means by which Hashem communicates with human beings ceased to be prophecy, and instead, we began to study, analyze, and interpret the Torah in order to determine what Hashem wants from us. Likewise, even though the Mizbe’ach functioned for several centuries more, the move toward prayer, tefillah, as the central mode of how we worship Hashem had begun.

It is no accident that the name for the group of Sages that ordained these shifts includes the word “knesset,” a word that means a gathering, an assembly, or, in Greek, a synagogue. The shift from prophecy to Torah reading and study, and the shift from sacrifice to prayer, also indicate a shift from a Temple-centered religion to one centered on local, decentralized, “miniature sanctuaries” that serve as a hub of such activities. And indeed, to this day, prayer and Torah study would probably be considered the two core functions of a synagogue.

It is therefore surprising to find the last member of the Anshei Knesset HaGedolah stating that the world stands on three pillars: “Shimon the Righteous was among the last of the Anshei Knesset HaGedolah. He used to say: the world stands upon three things: Torah, Avodah (worship), and Gemilut Chasadim (acts of kindness). We have seen that the Anshei Knesset HaGedolah took pains to ensure that Torah and Avodah would remain part and parcel of the Jewish way of life even when the Temple is far away or lies in ruins. The synagogue developed as the locus for these activities. And then along comes Shimon HaTzadik, at the tail end of this era, to say that there is a third element without which the world is unsustainable: acts of kindness. We would expect that this element, too, would become one of the core functions of the synagogue, and yet, even though there is so much Chesed in our communities, we do not usually associate these activities as part of the shul, or as one of its central purposes.

However, I believe that a close look at certain texts will show that this element has indeed been an integral part of the synagogue genome from the earliest times. Having established that, we will consider how to bring greater emphasis on this component of synagogue life.

Our journey begins with the earliest known synagogue inscription. Discovered in Jerusalem in 1913, the Greek-language inscription, which dates back to the time that the Second Temple still stood, recognizes a man called Theodotos for having built the synagogue:

Theodotos son of Vettenus, priest and head of the synagogue (archisynágōgos), son of a head of the synagogue, and grandson of a head of the synagogue, built the synagogue for the reading of the law and for the teaching of the commandments, as well as the guest room, the chambers, and the water fittings as an inn for those in need from abroad, the synagogue which his fathers founded with the elders and Simonides. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Theodotos was the “gvir” (or whatever the equivalent Greek term is) who built this synagogue in Jerusalem. He was the leader of this synagogue, the “archisynagogos,” as were his father and grandfather before him.

The inscription also tells us the purpose of the synagogue: reading the law (i.e., keri’at ha-Torah), explaining the commandments (likely the oral expounding of verses that were later collected into early collections of midrashim, like midrashei halakha), and providing for the needs of pilgrims: lodgings, perhaps a place to eat, and “water fittings,” which is likely a bathhouse or mikveh. The synagogue was something of an inn or hostel for travelers to Jerusalem from abroad. Surprisingly, this inscription does not mention prayer as one of the synagogue’s functions, perhaps because these pilgrims would pray or bring offerings in the Temple. In any event, this synagogue was not first and foremost a place to pray.

The next source comes from the more classic rabbinic canon: the Gemara in Pesachim (100b–101a). There is a dispute between Rav and Shmuel, two of the greatest Sages of the first generation of Babylonian Amora’im (third century CE), concerning whether the recitation of Kiddush on Shabbat must be in the place where the meal will be eaten. The Gemara asks why, according to Shmuel (who maintains that Kiddush must be in the place of the meal), is Kiddush recited in the synagogue? The answer echoes what we have already seen in the Theodotos inscription: “It is so that guests, who eat, drink, and sleep in the synagogue, may fulfill their obligation.” The practice of reciting Kiddush and Havdalah in the synagogue is still practiced outside the Land of Israel, but very few synagogues in Israel maintain this practice, on the grounds that nowadays guests do not eat and sleep in the synagogue. (Though it is worth noting that several Rishonim maintain that Kiddush should be recited in the synagogue anyway.)

Yet the Tosafot raise a challenge to this Gemara. Elsewhere (Megillah 28a) the Gemara states that it is forbidden to eat and drink in a synagogue, so how can the Gemara here state that guests eat, drink, and sleep there? The Tosafot themselves answer that the passage in Pesachim does not mean that the guests eat and sleep in the synagogue proper, but in adjacent rooms that are still within earshot of the main synagogue sanctuary. That is, the Tosafot imagine a synagogue complex with rooms that serve different functions—some for prayer and others to provide food and lodgings for guests.

Other Rishonim offer different answers. Ramban (cited by Ran) invokes the concept of “conditional” synagogues. Namely, a stipulation is made at the time of the synagogue’s construction allowing it to be used for other purposes when necessary. Thus, if no other space is available, visitors may eat and sleep there.

The most direct answer comes from Rabbi Yeshaya di Trani (thirteenth century) in his Tosafot Rid on Pesachim. He writes: “The townspeople are forbidden to eat and drink there, but guests are permitted to, for the whole purpose of their construction is so that guests traveling from place to place may rest there!”

Beit Yosef (Orach Chayim 671:18) extends this principle to Chanukah candles as well. In explaining why the custom is to light Chanukah candles in the synagogue, it states: “It seems that they instituted this for guests who have no home in which to light, just as they instituted Kiddush in the synagogue.” The mitzvah to light Chanukah candles applies to the household collectively, not to individuals. But what if someone has no home temporarily, and perhaps permanently? Such a person has a home in the synagogue, and it is there that they can fulfill the mitzvah of lighting Chanukah candles.

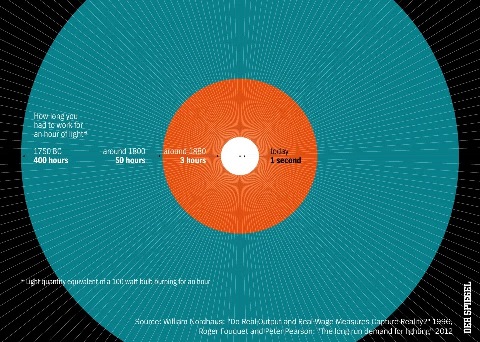

On the topic of light, it is worth considering other aspects as well. Specifically, light was expensive. The infographic above shows how many hours of work at basic wages could buy the equivalent of an hour worth of light from a 100-watt bulb. Barely 200 years ago, it demanded 50 hours of work; today, due to increase in income, better lighting technology, and cheap energy, one second of work buys that amount of light. This is an astounding improvement, and as a result we tend not to appreciate that the various mitzvot that involve candlelight demanded significant outlays.

But light has an advantage as well. It is easily shared. In the words of the Gemara, “ner le-echad, ner le-me’ah.” The same candle can provide light for one person or 100 people. This brings us to our next source, a responsum from Rabbi Yosef Colon (Teshuvot Maharik §9, fifteenth century). The custom in Italy was to give the first aliyah of Parashat Bereishit—which describes the creation of light—to the community member who pledged to cover the costs of oil for lighting the synagogue that year. If the donor was not a kohen, then all kohanim were asked to leave the synagogue for that aliyah.

The question arose regarding a kohen who did not pledge the costs of the oil but also refused to vacate his right to the first aliyah. The community eventually alerted the local authorities, who arrested the stubborn kohen. They then wrote to Maharik to ask whether they had done the right thing. Maharik answers in the affirmative, as by allowing for open competition for the prestige of this aliyah, not only does it demonstrate honor for the Torah, but it results in a greater abundance of oil, which benefits the entire community.

The circumstances described in this teshuvah introduce several more dimensions to our discussion. First, until now we have been discussing guests, people who have no place to eat or sleep. This responsum speaks of a different sort of chesed: the pooling or sharing of resources. The person who pledges to keep the shul lit makes an expensive resource available to the entire community—when he easily could have used that money to keep only his own home lit.

The second dimension introduced here is that there is an exchange. The donor pledges money for lighting, and the community “pays” him by bestowing on him a great honor. The synagogue becomes the site and even the vehicle of this exchange: the money flows to the synagogue, the honor is enacted in the synagogue—whether performatively, like the aforementioned aliyah or the Ashkenazic equivalent of Chatan Bereishit, or, as we saw in the case of Theodotos, by putting a name on a wall or building. Honor, bestowed by the synagogue community, functions as a currency that can be exchanged for resources that help the needy, whether those within the community or those visiting from elsewhere.

The implication here is that synagogues should have socioeconomic disparities. This is brought home by a Gemara in Sukkah (51b) that describes the magnificent synagogue of Alexandria. It records that members of the same profession—goldsmiths, silversmiths, tailors, etc.—would sit together in their own section. Thus, “when a pauper walked in, he would recognize his fellow craftsmen, and from there he would draw his livelihood and provide for his household.”

People found jobs in the synagogue, and offering someone a job is, according to Rambam, the highest form of tzedakah [charity]. To be quite frank, I have found work in shul, and I am far from alone. The synagogue is a place where people find summer internships and make connections. It is an incredible networking space (nisht af Shabbes geredt). In fact, I think this is one of the secrets of our communal success. It is not just that we help each other out. Coreligionists and neighbors often do that. Rather, it is precisely the fact that shuls contain socioeconomic disparities that create situations where the people at the higher end can provide opportunity with those at the lower end. Shuls where everyone is wealthy or where everyone is poor can be filled with chesed, but they do not provide the sort of upward mobility that comes from economic diversity within the synagogue, where wealthy and needy sit in the same pew, as in Alexandria.

This has played out in my own family. Seventy years ago, my grandfather, a new immigrant to the United States, was able to secure a mortgage, and thus build a foundation of economic stability, because several people in the synagogue where he served as shamash [synagogue assistant] and part-time cantor helped him out by giving interest-free loans and cosigning his mortgage. He put a lot of blood, sweat, and tears into making it in America, but he also had earned the trust of wealthier, more established members of the synagogue community, who came to his aid.

The elements that we have been discussing all appear together in yet another text: the “blessing for the congregation” recited after the Shabbat Torah-reading. Listed in the standard version of this blessing are “those who designate synagogues for prayer,” like Theodotos, as well as “those who provide oil for lighting, wine for Kiddush and Havdalah, bread for guests, and tzedakah for the poor.” These are all part of the synagogue’s DNA.

I would like to conclude this discussion with some practical suggestions about how these ideas can be translated into contemporary synagogues.

We should not be afraid of giving honor and respect to donors. It is okay to put a donor’s name on the building. It is part of an exchange, money for prestige. We can even bring back auctions, which seem to have fallen into disuse somewhat. It is okay that some congregants have more material wealth than others. On the contrary, the synagogue is at its best when there are disparities, when rich and poor sit together; on balance, this works in favor of the poor.

A friend of mine recently related how, growing up in Brooklyn, you knew there was a Kiddush that day if certain people showed up. Baalebatim grumbled about it and called them freeloaders, but these people would keep showing up wherever there was a Kiddush after Shabbat morning prayers. It was not until much later that my friend realized that these people probably did not have much food at home, and that this Kiddush was the best meal of the day for them. I think we should bear this in mind in our own Kiddush cultures. There are large shuls that allow for “invitation only” Kiddushes, and I find this very problematic (especially if the ba’alei simcha made the whole congregation suffer through extra aliyot, extra mi-sheberakhs, and tone-deaf Uncle Simcha’s rendition of Mussaf). Private Kiddushes belong in homes, not in synagogues. You never know who has fallen on difficult times and can benefit from not having to prepare a full Shabbat meal.

There are many kinds of “needy” people in the community. Another friend recently told me about synagogues in Florida that host luncheons every Shabbat because of congregants, especially elderly men whose wives are ill or deceased, who simply never learned how to prepare Shabbat meals for themselves. In communities with many older singles, those communal meals can help alleviate an abiding loneliness.

It is surely true that we must minimize talking during prayers, and that mundane speech is not allowed in the synagogue. At the same time, there are people in the synagogue looking for work, or for better work, and helping someone find a job is the highest tzedakah there is. We therefore need to develop a vocabulary that allows us to use the synagogue as a networking space without compromising its sanctity. This will not be easy, but we should not allow this function of the synagogue to atrophy.

We began our discussion with the Aron and Mizbe’ach, and it seems to me that the Gemilut Chasadim aspect of the synagogue is symbolized by the Menorah (candelabrum), which provides light, and the Shulchan (showbread table), which provides food, and that the way to invite Hashem into our communities is by providing hospitality to others.

This aspect of synagogue function, due to a variety of historical exigencies, has faded somewhat, so it is up to us to rethink how we can restore Gemilut Chasadim to its prominent place within the core functions of our synagogues.

With gratitude to Rabbis Uri Goldstein, Elli Schorr, and Daniel Yolkut, my dialogue partners while I was imagining this essay.

This website is constantly being improved. We would appreciate hearing from you. Questions and comments on the classes are welcome, as is help in tagging, categorizing, and creating brief summaries of the classes. Thank you for being part of the Torat Har Etzion community!